I wrote this text as a “web-only chapter” for Microsoft Exchange Server 2010 Inside Out , (also available at Amazon.co.uk

, (also available at Amazon.co.uk and as a Kindle edition

and as a Kindle edition , with other e-book formats for the book are available from the O’Reilly web site). Unfortunately the chapter doesn’t seem to have appeared on the O’Reilly web site and several people have asked me about the content so I am publishing a modified and updated version of it here – all comments are gratefully received.

, with other e-book formats for the book are available from the O’Reilly web site). Unfortunately the chapter doesn’t seem to have appeared on the O’Reilly web site and several people have asked me about the content so I am publishing a modified and updated version of it here – all comments are gratefully received.

– Tony

Moving Exchange into the Cloud

Over the last few years and gathering pace from the point where Microsoft announced Azure, Online Services, and new web-based version of some of the Office applications at the Professional Developers Conference in October 2008, one of Microsoft’s strategic imperatives is to be a major player in cloud-based computing. Chris Capossela, the Microsoft senior vice president with responsibility for Microsoft Office, has been widely quoted in interviews as predicting that 50 percent of the Exchange installed base will be online by 2013. Some of these mailboxes will come from the existing installed base and some will come through migrations of other email systems such as Lotus Notes. Other commentators such as the Radicati Group reckon that hosted email seats will grow by 40% by 2012, largely driven by deployments by small and medium companies but that large enterprises will increasingly analyze the value that hosted email can deliver, especially for regional offices.

Microsoft’s challenge during a transition to cloud-based services is to build and deliver their online services (then known as Microsoft Business Productivity Online Suite or BPOS and subsequently renamed in October 2010 to be Office 365) in a cost-effective manner and attract customers to use the new service while not eroding the installed base and the rich income streams that flow from traditional on-premises deployments of Office, Exchange, and SharePoint. Microsoft isn’t the only company that’s engaged in a balancing act. IBM is going through much the same process as it brings the Lotus suite into the cloud with LotusLive, including the iNotes hosted email platform.

Microsoft certainly has very good knowledge of some parts of the financial equation such as the cost of building and running the datacenters that they require to deliver online services, but the wild card is the cost of migrating customers and then maintaining service levels to meet tough service level agreements (SLAs). If they spend too much on migration, maintenance, and support, it will place enormous strain on Microsoft’s most profitable unit (the Business Division, responsible for $19.4 billion income in 2008). On the upside, if Microsoft gets online services right, they’ll generate ongoing and profitable success for the Office franchise that will help them fend off the competitive pressure from Google and other companies. Microsoft’s first progress report in November 2009 announced the acquisition of their first one million paying customers across a variety of market sectors. The success or perhaps increasing competitive pressure enabled Microsoft to decrease the monthly cost per user to $10 (in the U.S.) for the Office 365 suite and to eventually offer 25GB mailboxes running on Exchange 2010 servers at that price point. At the time of writing, Microsoft has not deployed Exchange 2010 as part of their online offering; this upgrade is expected sometime towards the middle of 2011 as part of the launch of Office 365. At that time online users will be able to take advantage of the enhanced functionality delivered by Exchange 2010. An article by Mary Foley in Zdnet.com includes an interesting graphic showing the timeline of the evolution of Microsoft’s online platform that I reproduce below:

Timeline for the evolution of the Microsoft Online platform

However, while Microsoft was reporting some success in terms of customer take-up, the financial side didn’t seem to be so pretty with some commentators such as Scott Berkun questioning the vast deficits that Microsoft has accrued in its Online Division (see the chart below). Some investment to build out the datacenters required to support cloud services is inevitable; the problem seems to be that the income from customers isn’t yet getting near to matching the expense line. We shall see how this story develops over the coming years.

Microsoft Online Division operating income

On the customer side, the increasingly tough economic conditions since the economic meltdown of 2008 have created an environment where companies are eager to pursue potential cost savings so the potential value of replacing an expensive in-house email system with an off-the-shelf online service that comes with a monthly known cost is an attractive notion. As customers assess the impact of Exchange 2010 on their infrastructures, it’s likely that Microsoft will encourage customers to assess online services as an upgrade option for their existing email deployment, especially if the customer currently operates older software such as Exchange 2003 where the migration to Exchange 2010 will be difficult and the technical learning curve for support staff is long.

In reviewing the options that exist for customers in the 2010-2012 timeframe, four major possibilities present themselves for companies that currently run Exchange:

1. Continue to operate an in-house deployment and upgrade to Exchange 2010. This includes variations such as traditional outsourcing to companies such as HP that operate Exchange in your datacenter or in their datacenter or using the approach taken by companies such as Azaleos, who place servers in client datacenters and manage the servers remotely.

2. Embrace the cloud and move mailboxes to be hosted in Microsoft Office 365. You will go through a migration phase to move mailboxes to the cloud, but eventually all the in-house servers that run Exchange will be eliminated. In-house servers will still be required to host Active Directory to provide federated authentication and other features that enable secure connections and data exchange with the cloud services as well as to run other applications that do not function in the cloud.

3. Take a hybrid approach and move users who only need the functionality delivered by a utility email service to Microsoft Office 365 while retaining part of the current infrastructure to continue to run Exchange for specific user populations who cannot move into the cloud, perhaps because of some of the reasons discussed here.

4. Explore other paths such as using a different online service (Gmail) or moving from Exchange to a different email system such as the Linux-based PostPath, recently acquired by Cisco. While PostPath boasts seamless MAPI connectivity for clients such as Outlook, Microsoft still has an inbuilt advantage in that the costs involved in moving users from Exchange may outweigh any of the potential benefits that can be reasonably accrued in the short term. Existing Microsoft customers are more likely to explore the possibilities in Microsoft Online where they retain a familiar platform and save costs that way than to plunge into the uncertainty that any migration entails.

New companies that do not have an email system installed today should absolutely consider the cloud for email services because this approach allows them to start to use email immediately, grow capacity on an on-demand basis, and take advantage of the latest technology that’s maintained by the service provider. Other interesting deployment scenarios include:

- Companies who want to migrate off their current email platform (for example, from Lotus Notes to Exchange 2010). The advantage here is that they can move to the latest version of the new platform technology very easily without incurring substantial capital costs. The announcement in March 2009 of the intention of Glaxo Smith Kline, a major pharmaceutical company, to move from Lotus Notes to Office 365 is a good example of the kind of platform migration that will occur.

- Companies who run earlier versions of Exchange and want to avoid the complexity and cost of a complete migration to Exchange 2010. For example, if a company runs Exchange 2000 or 2003 today, they have a lot of work to do before they can consider a migration to Exchange 2010 including updates to hardware, operating system, associated applications, and clients. Some of this work (such as client updates) still has to be done before it is possible to move to the cloud, but a move to a cloud-based service presents an interesting opportunity to accelerate adoption of the latest technology at lower cost.

Any company that has a legacy IT infrastructure and applications will have their own unique circumstances that influence their decision about how they should use cloud based services. Let’s discuss some of these issues in detail.

So what’s in the cloud?

One definition of cloud computing is “IT resources accessed through the Internet” where consumers of the resources have no obligation to buy hardware, pay software licenses, perform administration, or do anything else except have the necessary connectivity to the Internet to be able to access the service. Think about how you use consumer email services such as Hotmail or Gmail as both services fall into this category. The feat that Microsoft now wants to perform is to transform part of its revenue stream into funded subscription services for access to applications such as Exchange, SharePoint, and Office Communicator Server without cutting its own throat by eliminating the rich stream of software licenses purchased for traditional in-house deployments of these applications. At the same time, Microsoft knows that it has a huge competitor in Google who is driving the market to a price point that has attracted the attention of many CIOs, who now question how much they are paying for applications like Exchange. Google’s offering starts at $50 per mailbox per year and while the cost of a Google mailbox is usually higher when other features such as anti-spam (from Postini) are stacked on top of the basic mailbox, the headline figure is what attracts executive attention and causes customers to look at the Google model to see if it will work for them.

Apart from its low price point, Google paints a vision of reduced complexity, ease of deployment, and rapid innovation that creates a compelling picture especially for companies that have experienced difficulties with Microsoft software in the past. Perhaps they have had problems migrating from one version of Exchange to another; perhaps they don’t like the fact that they have to invest in new server hardware to move to Exchange 2007 and now may have to buy some more new servers to move to Exchange 2010; maybe the complexities of Software Assurance and other Microsoft licensing schemes has created an impression that they are paying too much for software. Or maybe it’s just because the CIO thinks that it’s time for a change and that a new approach is required that’s based on new technology and new implementation paradigms.

Whatever the reason that drives customers to look at competitive offerings, Microsoft has many strong points to call on when it responds. Its products are deeper and more functional than the Google equivalents and work well when deployed on-premises and in the cloud. Its client technology is more diverse and delivers a richer user experience through Outlook, Outlook Web App (OWA), and a range of mobile devices from Windows Mobile to the iPhone. By comparison, its inventor might love the Gmail interface, but it’s not quite OWA. Connecting Gmail to Outlook is possible but limited by use of IMAP. Calendars and contacts don’t quite get synchronized and the offline functionality available through Google Gears isn’t as powerful as Outlook with the OST and cached Exchange mode and the OAB. Some rightly criticize the often overpowering nature of the feature set found in Microsoft Office applications and point to the simplicity and ease of use of Google Docs, which is all very well until some of your users (like the finance department) want to use a pivot table or another advanced feature that’s ignored by 90 percent of the user community. Microsoft’s track record and investment in developing features for Office over the last 20 years creates enormous challenges for Google in the enterprise. Despite its undoubted strengths, Microsoft can’t afford to rest on their laurels and has to deliver applications that are price competitive and also feature rich. Cost is very much in the mind of those who will purchase applications in the future whether the applications are deployed in-house or in the cloud.

To achieve the necessary economics in the delivery of feature-rich applications at a compelling price point, the infrastructure to deliver cloud computing services is designed to scale to hundreds of millions of users, remain flexible in terms of its ability to handle demand, and to be multi-tenant but private. In other words, the same infrastructure can support many different companies but an individual’s data must remain private and confidential. It is difficult for developers to retrofit applications that were originally designed to function in a purely private environment to be able to work well in a multi-tenant infrastructure. For example, SharePoint’s enterprise search feature is very effective across a range of data sources within a single company. Making the same function work for a single company within a multi-tenant infrastructure requires a different implementation. Google designed its applications to work on a multi-tenant basis from the start whereas Microsoft has had to transform its applications for this purpose.

The different approaches taken by Google and Microsoft represent two very different implementations of cloud services. Google’s platform uses programming techniques such as MapReduce that they designed to build massively scalable applications that run on bespoke hardware. You can purchase services from Google but you can’t buy their code and deploy it in your own datacenter. On the other hand, Microsoft has an installed base to consider and needs to engineer applications that run as well on a hosted platform as they can when deployed by companies in private datacenters. Essentially, with the exception of some utilities required for identity management and data synchronization, Microsoft deploys the same code base (with some additional tooling) for Office 365 that a customer can purchase for applications like Exchange, SharePoint, and Office Communicator. The difference between private and hosted environment is the way that Microsoft uses automation and virtualization to drive down cost to a point where their applications can compete with Google. However, it’s fair to say that customers can adopt and use many of the same techniques in their own deployments of Microsoft technology to achieve some of the same savings, if not those open to Microsoft due to the massive scale that they operate on.

In addition to being able to keep their data private, companies can have their own identity within the shared infrastructure. In email terms, this means that a company can continue to have its own SMTP domain and email addresses and have messages routed to mailboxes that are hosted in the cloud or on in-house servers.

Cloud infrastructures are based on different operating systems (Linux is a popular choice), but their operators put considerable effort into simplifying and securing the software stack that they use to drive performance and reliability. These infrastructures focus on scaling out rather than scaling up, preferring to use thousands of low cost servers rather than fewer large servers. Applications are built using open and well-understood standards such as SMTP, IMAP, POP3, HTTPS, and TLS so that as many users as possible can connect and use them. Google uses its own version of Linux running on commodity “white box” hardware, its own file system, storage drivers, and its own applications to deliver a completely integrated and fit-for-purpose cloud computing platform. In many respects, you can compare the integrated nature of Google’s platform with that delivered by the mainframe or minicomputer in the 1980s and 1990s. As you’d expect, Microsoft’s cloud platform is based on Windows and .NET development technologies, albeit with a high degree of attention to standardization and virtualization to achieve the necessary efficiency within the immense datacenters used to host these services.

Why moving Exchange to the cloud is feasible

Over the last few years, it has become increasingly feasible for enterprises to consider including cloud platforms as part of their IT strategy. Greater and cheaper access to high quality Internet connections, the work done by companies such as Google to prove that high-quality applications function on the cloud platform, the growing share of consumer spend taken by web-based stores, and the comfort that people have in storing their personal data in sites such as Mint.com (financial data) or Snapfish.com (photographs) are three obvious examples of how cloud-based services work. In terms of Exchange, three developments are worth noting:

1. Experience with consumer email applications such as Hotmail, Gmail, and Yahoo! Mail has created familiarity with the concept of accessing email in the cloud. Almost every person who works in a company that uses Exchange has their own personal email account that runs on a cloud platform and while the majority of client access is through web browsers, some users connect with other clients including Outlook. While some service outages have been experienced, the overwhelming experience for an individual user is usually positive (especially because these services are free). This then leads to a feeling that if it’s possible to host personal email in the cloud, it should be possible to host email for enterprises. Of course, this assertion is technically true until you run into the extra complexities that large organizations have to cater to that individuals do not.

2. The advent of RPC over HTTP and the elimination of the requirement to connect to corporate email systems via dedicated VPNs demonstrates that it is possible to securely connect clients to email across the Internet. We’ve had this capability since Microsoft shipped Outlook 2003 and Exchange 2003 and while the early implementations took a lot of work to accomplish, Microsoft greatly improved the setup and administration of RPC over HTTP in the Outlook 2007 and Exchange 2007 combination. RPC over HTTP is widely used today to allow users to connect Outlook to Exchange across the Internet.

3. Outlook (2003 to 2010) running in cached Exchange mode is now the de facto deployment standard in the enterprise. Cached mode creates a copy of a user’s mailbox on a local disk and insulates them from temporary network outages by allowing work to continue against the local copy that Outlook constantly refreshes through “drizzle mode” or background synchronization with the server. The nature of the Internet is that you are more likely to experience a temporary outage than inside a corporate network. Cached mode is therefore important in terms of maintaining a high level of user confidence that they can continue to get their work done while connected to the cloud.

Some companies have already explored their own variation of cloud by using the Internet to replace expensive dedicated connections between their network and a hosting provider and have a good understanding of the challenges that need to be faced in moving to the cloud. Others will never move from in-house servers because of their conservative approach to IT, fears about data integrity, the regulatory or legal compliance required of certain industries (for example, the FDA requirement to validate systems used by pharmaceutical companies for anything to do with drug trials), the unavailability of high-quality or sufficient bandwidth to certain locations, or because they operate in countries that require data to stay within national boundaries. Other companies are champing at the bit and ready to move to Office 365 as soon as they can, perhaps because they are running an earlier version of Exchange and see this as a good way to upgrade their infrastructure. In all cases, it’s wise to ask some questions about the readiness of your company to operate email in the cloud so as to arrive at the best possible decision. Let’s talk about some of the questions that are worth debating.

Types of deployments

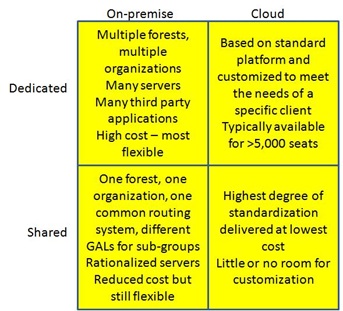

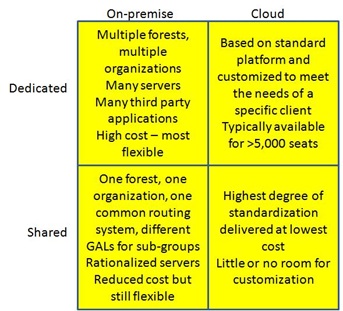

Before anyone can move from a traditional on-premises deployment to use a cloud-based service, they need to understand the way that they use the application that they are considering for transition to make sure that the cloud-based service can deliver the same degree of functionality, reliability, and compliance with regulatory requirements. The following figure illustrates a simple categorization of Exchange deployments into four basic types of deployment.

Types of Exchange deployments

Types of Exchange deployments

Dedicated on-premises deployments are those that are sometimes found in very large conglomerates where different operating units have the ability to create and operate their own Exchange organization. The deployment model is very flexible because Exchange can be tailored to meet the needs of the operating unit. However, it is expensive in terms of software licenses, operations, and complexity (multiple deployments of Windows, Exchange, and third-party applications) and cannot usually be justified unless an operating unit has a real business requirement to run its own service.

Shared on-premises deployments are the more usual model within large companies. A single Active Directory forest supports a common Exchange organization. Some tailoring of Exchange may be done, such as the provision of different GALs for specific operating units, but generally all operating units share a common infrastructure that can be rationalized and tuned to deliver a reliable and robust service.

Dedicated cloud deployments mean that the service is delivered from an infrastructure that is not shared by any other customer. The infrastructure might share a common datacenter fabric but the service provider ensures sufficient security to block access to the servers to anyone but the customer. While the service provider attempts to extract economies of scale from as many common components as possible, it is clearly more expensive to setup and operate dedicated servers for a customer and this cost is passed on to the customer in the form of higher monthly charges. Because the infrastructure is dedicated, it can be customized to meet specific needs at an additional cost.

Shared cloud deployments mean that all customers access a service delivered from a multi-tenant shared infrastructure. Costs are lowest as the service provider delivers a well-defined set of functionality that cannot be customized and they can spread the cost to create and operate the infrastructure across many different customers.

Once we understand the nature of the current on-premises deployment and the kind of cloud service that may provide the target environment, we can move to a discussion of the services offered by Microsoft.

What Microsoft can deliver

The first set of hosted email services delivered by Microsoft first delivered filtering, encryption, and compliance services to supplement on-premises customer deployments using a mixture of Exchange 2003 and Forefront technology. These services are useful but not mainline. Full-scale hosted email from Microsoft began with Exchange 2007 and the pace accelerated enormously with the introduction of Exchange 2010. Microsoft gained much experience from their Live@EDU implementation that provides Office services, including Outlook Live, to the education sector. Behind the scenes, Outlook Live connects to Exchange 2010 mailboxes. Live@EDU used beta versions of Exchange 2010 and has since upgraded to keep pace with software development. The use of Exchange 2010 in Live@EDU provided Microsoft with a terrific environment to gain knowledge of how to provision, operate, and manage large-scale hosting environments.

Hosted services focused on business rather than education usually have more stringent terms and conditions, including financial penalties for non-compliance with a committed level of service. Microsoft offers two flavors of hosted email within BPOS: dedicated and standard. Both versions ran Exchange 2007 initially and are scheduled to be upgraded to Exchange 2010 during the move to the Office 365 platform in early 2011 (many of the enhancements in SP1 such as the expanded range of features accessible through ECP are particularly valuable in a hosting environment). The dedicated offering is targeted at large enterprises and is only available to customers that have 5,000 mailboxes or more, probably because it is not worthwhile to create a dedicated environment including components such as network, hardware, help desk, security, and directory synchronization for less than this amount. The dedicated version is not multi-tenant because the hardware that supports a customer is literally dedicated and not shared with anyone else. The dedicated version also permits the customer to customize the service that they receive and is more expensive than the standard version for this reason.

Office 365 Architecture

The standard offering offers mailboxes that are supported on a multi-tenant infrastructure. In other words, all of the mailboxes are hosted on the same set of servers and use the same directory with logical divisions in place to appear that the mailboxes and directory (GAL) are quite separate. In 2008, Microsoft launched hosted email services with a promised 99.9 percent scheduled uptime and the same guarantee exists today for Office 365. The standard service has a number of optional added-cost extras including BlackBerry support, archiving, and migration from another email system. Windows Mobile (6.0 and later) devices are supported along with Outlook (the minimum version required is Outlook 2003 SP2), OWA, and Entourage (the EWS version is required to connect to Exchange 2010). Because it is dedicated to just one customer, the dedicated offering is more customizable and flexible and includes aspects such as business continuity and disaster recovery.

Hosted Exchange is not something new; specialized hosting companies have offered email services based on Exchange going back as far as Exchange 5.5. These companies have worked around the various shortcomings that exist in previous versions of Exchange to provide a cost-effective service to customers. Microsoft’s entry into the hosting game creates a new competitor, which isn’t good news for hosting companies, even if it substantially validates hosted email in the eyes of many. The aggressive “all you can consume for one low price” approach being pursued by Microsoft and Google to attract customers to use their online services will also force third-party hosting companies to reduce their operating costs and prices and could impact the profitability as well as the viability of some hosting companies. On the positive side, the emergence of Microsoft’s own hosted offerings and the emphasis that Microsoft executives have given to these services in the market adds credibility to the notion of sourcing email and collaboration services from the cloud and creates a new impetus for IT managers to consider this approach as they review their long term plans for applications such as Exchange and SharePoint.

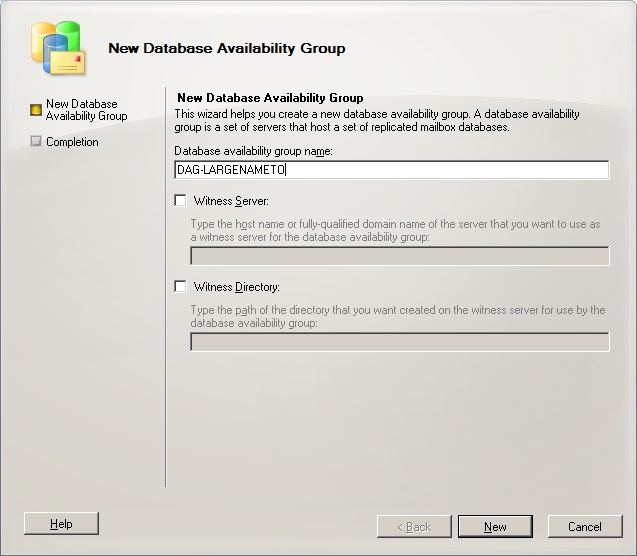

Microsoft engineering groups are busy making sure that the widest possible feature set works for large multi-tenant environments. A lot of this work involves adding new features to enable a better distributed management mode so that companies can manage their data on remote servers as easily as they can manage their own servers today. Exchange 2010 SP1 is a very manageable multi-tenant platform that blurs the boundaries of a messaging server that runs on both-premises and cloud services. The introduction of remote PowerShell has created a management framework that works equally well for local and remote servers. Other major advances to support hosted environments include:

- Administration across on-premises and hosted objects through the Exchange Control Panel, a new SLA dashboard, EMC, and remote PowerShell.

- A very functional web browser client (Outlook Web App – OWA) that supports many different browsers. The latest version of OWA as featured in Exchange 2010 SP1 is likely to be very similar to the browser used by Office 365 users.

- Microsoft Services Connector to enable federated identity management required to support single sign-on for users across the on-premises and hosted environments.

- Directory Synchronization (GALSYNC) to ensure that the GALs presented to on-premises and hosted mailboxes deliver a unified view of the complete company. This tool supports multiple on-premises forests. The out-of-the-box capabilities of GALSYNC are pretty simple and companies might have to purchase a more comprehensive directory synchronization product such as Microsoft Identity Lifecycle Manager (ILM) to handle complex environments such as the integration of addresses from multiple email systems.

- Microsoft Federation Gateway to support calendar (free/busy) and contact sharing, federated RMS, and message tracking across on-premises and hosted environments.

- Mailbox migration between on-premises and hosted environments, including the ability to avoid a complete OST resynchronization after moving a mailbox to the cloud platform. Mailboxes can be moved from Exchange 2003 SP2, Exchange 2007 SP2, and Exchange 2010 on-premises servers to Office 365 and back to an on-premises server again.

- Federated message delivery to protect the transmission of messages between on-premises and hosted environments. You can think of this as a form of secure messaging channels for users in that messages are encrypted and routed automatically between the two environments. When messages arrive in the environment that hosts the recipient mailbox, they are validated, decrypted, and delivered to the final recipient. Outbound messages can be routed through an on-premises gateway.

- Support for Outlook content protection rules (for Outlook 2010).

- Hosted Unified Messaging enabled by connecting on-premises PBXs with Microsoft Office 365 via IP over the Internet.

Note that at least one on-premises Exchange 2010 SP1 server is required to support mailbox migration, federated message delivery, and federated free/busy. The Microsoft Services Connector is installed as an IIS website on an on-premises server. It’s also worth noting that Microsoft runs a slightly different version of Exchange 2010 SP1 in its datacenters to support multi-tenant environments. The changes between this version and the version used for classic on-premises deployments are minor and are there to allow Microsoft to manage the different Exchange organizations that function in the environment. A good example is that many of the Windows PowerShell cmdlets have an –Organization parameter to allow an administrator to select objects that belong to a specific organization or to apply a new setting to selected objects. For example, in the Microsoft datacenter, you could fetch details of the default ActiveSync policy for the ABC Corporation organization with:

Get-ActiveSyncMailboxPolicy –Id “Default” –Organization “ABC Corporation”

There are also parameters on some PowerShell cmdlets that are only accessible to Office 365 datacenter administrators. For example, the Set-UMAutoAttendantcmdlet has parameters for default call routing that only work if you have the appropriate RBAC permissions in Microsoft’s data centers.

With the release of Exchange 2010 SP1, the only major feature gaps that now exist are lack of support for earlier Outlook clients and depreciated APIs such as WebDAV. Customers who depend on these features will have to upgrade or drop them before they can move to Office 365.

Federal support

In late February 2010, Microsoft announced delivery of BPOS Federal, a special version of the online suite tailored to meet the requirements of the U.S. government. BPOS Federal includes Exchange Online, SharePoint Online, Office Live Meeting, and Office Communications Online hosted in separate secured facilities where access is limited to a small number of U.S. citizens that have been cleared through background checks complying with the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR).

BPOS Federal is upgraded to address other regulatory requirements such as compliance with the SAS-70 (type II) auditing requirement, Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) 140-2, and ISO 27001. Large international companies often have the same requirements and the ability to comply with SAS-70 audits and deliver an ISO 27001 level service will reassure many who are nervous about the movement of IT into the cloud. Microsoft will also support two-factor authentication and enhanced encryption to meet the requirements of the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA ).

Users

You should review the needs of any special user groups that exist in your organization and determine whether their needs can be met in the cloud. For example, companies often take special measures to ensure the highest degree of confidentiality and service for their most important users. They place the mailboxes of their executives on specific servers that are managed differently from “regular” systems. Administrative access is confined to a smaller set of administrators, the servers might be placed in different computer rooms, and special operations procedures might apply for backups and high availability. While you can expect Microsoft to do a comprehensive job of securing data as it moves from clients in your network to servers in the cloud, data security will remain a concern as we go through the transition from an in-house world to the cloud and this is especially true when dealing with the kind of highly confidential data that circulates in executive email.

Another issue to consider is how users work together. For example, can users continue to enjoy delegate access to calendars and other mailbox folders in a mix of in-house and cloud deployment or do you have to keep users who need to share data on the same platform? Are there limits to the number of calendars that a user can open? Are there any problems with shared mailboxes or resource mailboxes or mailboxes that are used by applications? These are questions with no good answers today because we don’t have the final version of the cloud software to test against. However, they are good illustrations of the kind of thought process that you need to go through to understand the full spectrum of user requirements from basic mailbox access to sophisticated use of advanced features delivered by Outlook and Exchange.

Support

Part of the usual negotiation with a cloud services provider is the conclusion of a Service Level Agreement (SLA) that describes the level of availability of the service (for example, 99.99 percent), how outages are handled, and the financial compensation that might be due if a service does not meet the contracted uptime. Agreements like this are very common in outsourcing contracts, so it should not come as a surprise to apply them for cloud services. However, agreeing on an SLA is easy. Monitoring end-to-end performance for email and understanding the roles that local and cloud support play is more complicated. Because of this factor, many service providers will only guarantee an SLA within the confines of their own datacenter.

Local support is provided by the company and usually covers issues such as the company’s own network, connectivity to the Internet, client software, and integration with other applications that may depend on email. Cloud support comes from the service provider. The vast majority of support activity is performed locally and contact with the service provider should really only happen when the service is unavailable for a sustained period, such as three significant outages that affected user access to Google’s Gmail service for several hours in August 2008. Other smaller problems followed to disrupt service and then Gmail experienced another major outage in February 2009 after Google introduced some new code during routine maintenance in their datacenters. The code attempted to keep data close to users (in geographic terms) so that users would not have to retrieve mailbox data across extended links (http://gmailblog.blogspot.com/2009/02/update-on-todays-gmail-outage.html). The upside in the fix was the potential for better performance, but the downside of the failed update was erosion in user confidence in the Gmail service. Further Gmail outages followed in April 2009 and September 2009, the second of which occurred after Google made some adjustments to their infrastructure that were intended to improve service!

Microsoft has not been immune from service outages and experienced some hiccups in January 2010 with some anecdotal evidence pointing to problems with the network infrastructure and Exchange 2007 being at the cause (Microsoft hadn’t upgraded BPOS to use Exchange 2010 at this point). All of this proves that even the largest and best managed companies can sometimes take actions that disrupt service; and that those errors are magnified many times when the service is being consumed by millions of users.

Given how the Internet connects your network to the cloud, you can expect transient network hiccups that cause clients to lose connectivity from time to time. After all, no one is responsible for the Internet and no one guarantees perfect connectivity across the Internet all the time. That’s why cached mode Exchange is such a valuable feature of Outlook. Problems happen inside networks, even those that are under the sole and exclusive control of a single company. You have to be able to understand where local problems are likely to occur and how to address them fast before you escalate to the service provider to see whether the problem is at their end. For example, an outage may occur in your network provider that links you to the Internet, a firewall or router might become overloaded with outgoing or incoming connections and fail, or a mistake in systems administration might block traffic outside your network. The real point here is that if you move email to the cloud, you cede the ability to have a full end-to-end picture of connections from client to mail server and only have control over the parts that continue to reside inside your network. Users will hold the local help desk accountable when they can’t get to their mailboxes and that creates a difficult situation when you cannot trace the path of a message as it flows from client to server, you cannot verify that connections are authenticated correctly everywhere, and so on. In fact, because there are so many moving parts that could go wrong, including the Internet link, it is very difficult to hold a service provider to an SLA unless there is unambiguous proof that the cloud service failed.

Experience will prove how easy it is to manage availability in the cloud. For now, there is a weakness in management and monitoring tools to allow administrators to verify that an SLA is being met whenever an application relies on connectivity outside the network boundary that the organization controls. Indeed, problems exist in simply getting data from the different entities that run the corporate network, intermediate network providers, and the hosting providers in a form that can be collated to provide an end-to-end view of how a service operates. It may be possible to get data from one entity or another, but the data is likely to be inconsistent with data from other entities, impossible to match up to provide the end-to-end view, or uses different measurements that makes it difficult to synchronize.

Service desk integration is another related but different issue.You probably need some method to route help desk tickets from the system currently in use to the service provider and maintain visibility to the final resolution of the problem. Given the wide variety of service desk systems deployed from major vendors such as IBM, CA, and HP and the lack of standards in this area, this isn’t an easy problem to solve.

Software upgrades

One advantage of online services cited by their supporters is that software is automatically updated so that you always use the latest version. You don’t have to worry about testing and applying hot fixes, security updates, service packs, or even a brand new release of Exchange. Everything happens automatically as Microsoft rolls out new software releases on a regular basis across their multi-tenant datacenters.

The vision of “evergreen” software is certainly compelling. It can be advantageous to always be able to use the latest version of software, but only if it doesn’t increase costs by requiring client upgrades. For example, Exchange 2010 SP1 doesn’t support Outlook 2000 clients and sets Outlook 2003 SP2 as its minimum supported client. Outlook 2010 is required to access the full range of features offered by Exchange 2010 SP1. Therefore, to move to a hosted service based on Exchange 2010 SP1, you have to be sure that all of your users are happy to use OWA or that you have deployed a client that is fully compatible with Exchange 2010 SP1, even if some functionality is unavailable to supported clients such as Outlook 2007. Microsoft BPOS requires companies to deploy Outlook 2003 SP2 at a minimum and I expect that Office 365 will require Outlook 2007 as a minimum when it is deployed.

Looking into the future, you can predict that the same situation will exist. OWA clients will be automatically upgraded through server upgrades but administrators will have to ensure that “fat” clients like Outlook can connect. You can only expect Microsoft to provide backwards compatibility for recent clients, so you can expect to have to plan for client-side upgrades whether you decide to use in-house or hosted versions of Exchange, especially if you want to use some of the new features in Exchange 2010 SP1 such as MailTips that are not supported by older clients.

The problem here is that you have complete control over upgrades when you run in-house Exchange servers while you cede control to the hosting provider when you use an online service. A decision made by the hosting provider to apply an upgrade on their servers might have the knock-on effect of requiring customers to either accept lower functionality or, in the worst case scenario, accept the inability to connect with the client software running on some or all of their desktops. On the other hand, a software upgrade initiated by the service provider might introduce some new features that pop up on client desktops. This is great if the feature works flawlessly and the help desk knows about it in advance so that they can prepare for user questions, but it’s not quite so good if it causes panic for the help desk. Traditional outsourcing companies are usually slow to deploy new technology because of the cost and disruption to operational processes and users, so it will be interesting to see how quickly cloud hosting companies deploy new versions and how easily their users can cope with change.

Forced upgrades to new versions of desktop software might be an acceptable price to pay to be able to exploit online services. However, no administrator will be happy to be forced to upgrade clients (or to even apply a service pack or hot fix) without warning or consultation. This is a downside of using a utility service—you have to accept that you have to upgrade systems to maintain connectivity. To use an analogy, after they purchase an older house, consumers often find that they are required by electric companies to upgrade the wiring to maintain compatibility with the electricity service. You don’t have a choice here unless you want to run the risk that the wiring in your house will cause safety problems, including the ability to self-combust. You simply have to bring wiring and fittings up to code. Another example is the changeover to digital television in the United States which required consumers to either upgrade their TV or buy a converter box to retain service.

The bigger the client population in an organization, the larger the costs to deploy or upgrade and the more difficult it will be to ensure that everyone runs the right desktop software. Enterprise administrators are aware of the need to synchronize client and server upgrades and plan upgrades to match the needs of their organization. For example, no one plans an upgrade to occur at the end of a fiscal year when users depend on absolute stability in their email system to send documents around, process orders, and finalize end of year results. A forced and unexpected upgrade at this time could have enormous consequences for a business. Enterprise administrators also know about the other hidden costs that can lie behind client software upgrades such as the need to refresh complete Office application suites (you can deploy Outlook 2007 without deploying Office 2007 if you don’t want to use Word 2007 as the editor), the need to prepare users for the upgrade, and a potential increase in support costs as help desks handle calls from users who find that they don’t know how to work with the new software.

In an online world where services are truly utilitarian in nature, you might not have the luxury to dictate when client upgrades occur unless you use browser-based clients like OWA. Consumer-oriented email services like Hotmail and Gmail have always focused on web clients and therefore haven’t had to synchronize client and server upgrades. In fact, both Hotmail and Gmail have upgraded the user interface significantly over the last few years to add different features and change screen layouts. These changes are good in that they increase functionality but they also create a challenge for corporate help desks that have to support users who don’t understand why an interface has changed. Perhaps we will all be able to use web clients in the future and eliminate fat clients like Outlook. Until this happens online service providers will have to work out how to perform software upgrades on their servers without forcing client-side upgrades on their customers.

Applications

It’s common to find that email is integrated with other applications, including Microsoft products like SharePoint Online and Office Communicator Online that might be delivered from the cloud, but also applications that have been built in house and those that rely on commercial software such as SAP or Oracle. For example, you might find that your Human Resources (HR) department has integrated PeopleSoft with Active Directory and Exchange so that the process of creating a new employee record also includes the provisioning of their Windows account and an Exchange mailbox. Understanding the points of integration and how email has been “personalized” by the organization is an important part of determining whether a cloud approach is feasible for a company. To many companies, Exchange is much more than an email server and the more a company integrates email into business processes, the harder it becomes to make a fundamental change to the email platform, whether it is to move to a new email system, upgrade to a new release of a server, or to move to a new platform. Every application needs to be tested to ensure that it will continue to work during and after the migration.

Anyone who has been through a platform upgrade will tell you that the IT department usually underestimates the number of applications in use within a company. The IT department certainly knows all about the headline applications that they have responsibility for, but they probably don’t have much knowledge about the applications developed by individual users and workgroups that become part of business processes. IT probably knows even less about how applications are connected at the workgroup level.

These applications range from Excel worksheets to Access databases to web-based systems that are used for a myriad of purposes. They often only come to light when the IT department launches a project to upgrade the client or server platform to a new software release and a user finds that their favorite application no longer works. We saw this happen when companies upgraded their server platform from Windows NT to Windows Server 2000 and from Windows Server 2000 to 2003. The same experience occurred on client platforms, including upgrades of the Microsoft Office suite where macros in Word and Excel didn’t work in the new release or Access databases needed some rework to function properly. Given this experience, part of any preparation to move Exchange into the cloud should be a careful consideration of all the ways that email is used across the entire company to ensure that everything will continue to work after the transition.

Unified communications poses real challenges for hosting providers. The delivery model for hosted services is based on standardization, yet unified communications can involve telecommunications components from many different providers, some of which are relatively new and support the latest protocols and some that are approaching obsolescence and were never designed to operate in a TCP/IP-centric world. If you want to move to a hosted environment, you can rip and replace to move your telecommunications infrastructure to supported platforms or find a hosting partner that is willing to accommodate your existing platform.

No discussion about applications and Exchange can ignore public folders, the last remnant of Microsoft’s original vision for Exchange as a platform for email and collaboration. Microsoft has consistently signalled its intention to move away from public folders since 2003 but customer reaction has forced them to keep public folders in the product and to commit to their support ten years after the release of the last product version to formally include public folders. Given that public folders are still firmly in place within Exchange 2010 SP1, you can assume support until at least 2020. Companies that have thousands of public folders holding gigabytes of data that they use for different purposes from archives of email discussion groups to the storage for sophisticated workflow applications have some work to do to figure out how their specific implementation of public folders functions in a cloud environment. For example, can a mailbox in the cloud access the contents of a public folder that’s homed on an in-house server? If the public folder uses a forms-based application, can the same mailbox access the form and load it with the right data to allow the user to interact successfully with the application? However, Microsoft does not support public folders in Exchange Online. The notion of support for customizable applications based on public folders runs totally opposite to what you want to achieve from a service delivered through a utility-based multi-tenant infrastructure – a bounded set of functionality delivered at a low price point that is achieved through massive scale because everyone gets the same service. Companies that use public folders have three options:

1. Continue with their current deployment.

2. Keep servers in-house but use some aspects of the cloud such as using the Internet instead of dedicated communications.

3. Drop public folders,migrate their contents to another platform, and then move to Microsoft Online.

Much the same problem occurs when you consider aspects of other Microsoft applications such as OWA customizations (for example, changing the log-on page to display your corporate logo) or SharePoint web parts that are needed for an application. Utility services are just that – a utility. You wouldn’t expect to be able to ask the water or electric company to deliver you a custom service, so you shouldn’t expect to be able to ask Microsoft to deliver your customized form of Exchange or SharePoint from their utility service. It’s entirely possible that Microsoft will figure out how to allow companies to customize different aspects of online services in the future but I don’t expect this to be part of the offering we see in the next few years.

Privacy and security

Companies that move part of their infrastructure to the cloud assume that the cloud providers will protect their confidential data to the same extent as is possible when that data resides inside the company’s firewall. Consumers have long been happy to upload even their most private information (email, documents, photos, PC backups, and financial data) into the cloud, perhaps because they do not quite understand how the data is secured and protected against inadvertent exposure. There have been instances when consumer data was compromised through service provider errors. For example, http://www.techcrunch.com/2009/03/07/huge-google-privacy-blunder-shares-your-docs-without-permission/ describes one instance when Google documents were shared with other users without their authors’ consent.

The underlying problem is that the effect of a vulnerability discovered within a company’s own firewall is limited to the processes that the company has put in place to handle this type of security outage. When a breach occurs in the cloud, you have no control over how the service provider addresses the problem and can only deal with the effect of the breach. The net effect is that cloud platforms remove one layer in the defence in depth strategy that companies have deployed to protect their data because a breach that they might have avoided through their own security processes could affect them along with everyone else that shares the same infrastructure. In general, consumers don’t worry too much about this problem because they have benefited greatly from the advent of cloud-based services. Consumers get a service that is generally free while the service providers build an audience for advertising and a platform that they can sell to other constituencies.

The security and privacy issues that companies have are enormously complex when compared to those of an individual consumer, who doesn’t have obligations to shareholders,the market, regulatory organizations and government, customers, employees or retirees. Another barrier for corporations is the willingness to allow proprietary information to be stored on computers that they have no control over. Email is used as a vehicle to circulate vast amounts of data between users including attachments of all types and content. Budgets, new product plans, details of potential acquisitions, HR information, strategic plans, and designs are just some of the kinds of information that might be included in worksheets, presentations, and documents attached to email. Companies are quite happy when this information is under their control and go to enormous effort to ensure that users understand the consequences of releasing proprietary secrets externally. It takes a leap of faith to be able to achieve the same degree of happiness when company secrets reside on servers in a datacenter that is not under the company’s direct control.

Outsourcing providers address security and privacy concerns by dedicating space to customers in datacenters that are owned and managed by the outsourcer or the customer. The dedicated space holds the computers and other infrastructure to host the applications and data. The operators that look after these systems have probably performed the same work for years and have great understanding of the importance of the data to the company. Experience accumulated over decades of outsourcing has created a security environment and methodology to protect even the most sensitive data that a company might possess.

Things are different in the cloud because dedicated infrastructure is a rarity rather than the norm. Instead, everyone’s applications and data run on multi-tenant infrastructures in huge datacenters. It’s certainly possible to isolate data that belongs to a specific company but the economics of large-scale cloud hosting seeks to eliminate cost whenever possible to deliver a service at the lowest possible price point so operations staff will have little real knowledge of the companies that they serve and the importance of their data and applications to these companies. An inadvertent slip by the operations staff could expose the data belonging to many companies and no one might know until too late. Data belonging to a company under SEC supervision might be intermingled with data belonging to companies that have to comply with U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations. All can be affected by a single software bug or administrative foul-up. This risk is acceptable for private individuals who store their personal email on a service such as Gmail, but senior executives might take a different view if they are asked to store email that contains extremely confidential information on the same service. Think of the issue in this way: no great harm really accrues if Jane’s working document about family holiday plans is inadvertently exposed to others through a software or operational failure. Great harm to a company may accrue if a document describing the terms of a potential take-over is revealed through the same failure. Companies that want to move to the cloud have to take this risk into account when they make their decision and be absolutely sure that the service provider has taken all reasonable steps to ensure that no such problem will occur over the lifetime of the contract.

Keeping corporate secrets intact is clearly important but sometimes even corporate secrets have to be revealed as the result of legal action. Taking the steps to search a mail system for specific documents in response to a legal discovery request is reasonably straightforward for an on-premises deployment but might only be possible at additional cost or with an extended deadline on a cloud platform.

Another issue worth considering is the physical location of the data. For example, if the data resides in a datacenter in the United States, it comes under the prevue of the USA PATRIOTAct that permits U.S. law enforcement agencies to search electronic data. This fact probably doesn’t enter the mind of a CIO as they listen to a pitch on the wonders of the cloud but it serves to illustrate that moving data around can expose companies to new supervision and regulatory oversight that they hadn’t considered. Companies that consider a move to a cloud platform therefore have to satisfy themselves to the overall security regime of the service provider, how the service provider protects the privacy of the company’s data (including compliance with any country-specific requirements relating to employee and customer data), and the procedures and service level agreements that apply for common circumstances such as legal discovery, protection of data against virus infection, protection of users against spam and other irritants, and end-to-end security from client to server including transmission across the Internet.

Costs

A reduction in hardware costs is an anticipated advantage of moving work into the cloud. You won’t have to deploy servers and storage to host applications. You should also gain by paying less for software licenses for the servers. This isn’t just a matter of Exchange server licenses; it’s also the Windows server licenses and any associated software that you deploy to create an ecosystem to support Exchange. Common examples of third-party products that often run alongside Exchange include anti-virus, monitoring, and backup products, all of which have to be separately investigated, procured, deployed, and maintained. Your overall spend on software should be more efficient because you will pay for mailboxes that are actually used rather than for the maximum number of licenses that you think you need.

However, additional costs will arise in a number of areas. You’ll have to pay for the work to figure out how to synchronize your Active Directory with the hosting provider, how to transfer mailboxes most efficiently, and how to change your administrative model to work in the cloud. It’s also likely that the network connection that you currently use to the Internet is sized for a particular volume of traffic. That volume will grow as you transfer workload into the cloud. Traffic generated by applications that once stayed inside the organization will have to be transported to Microsoft and perhaps back to your network. Depending on the online applications that you subscribe to, this traffic includes sending email between users in your company, authentication requests, access to SharePoint sites, Office Communicator connections, and so on. Directory synchronization and other administrative traffic will make additional demands as will the need to move mailboxes during migration.

The point is that you cannot plunge into the cloud if you aren’t sure that your network has sufficient bandwidth to cope with the new traffic and the necessary infrastructure to handle the load of authenticated connections that will now flow into and out of your company. Firewalls, routers, and other network components might need to be upgraded and you might need to pay for additional software to handle network monitoring and security.

Datacenter and other capital expenditure is another aspect of cost to consider. Many companies make long-term capital investments in datacenters and IT equipment (servers, storage, network switches, and so on) and expect to leverage that investment over many years. This cost is already on the balance sheet and will be incurred even if it is not used unless it can be sold to a third party, which is difficult to do for datacenter space and used IT equipment. It might not be cost effective to move to a cloud-based solution until these capital costs are fully written off, or indeed to take the accelerated depreciation on any capital equipment that might be nullified by the move to a cloud-based service. On the other hand, a company that is reviewing new capital investment in IT should consider how cloud services affect their plans so as to optimize expenditure over investments that have to be made to support IT infrastructure that cannot be moved to the cloud and the purchase of cloud-based services. The cost of on-boarding services must also be considered as user mailboxes will not migrate themselves into the cloud automatically and some process and effort has to be put in place to coordinate and manage the transition.

The need for a back-out plan

Many things can happen that would force you to consider moving away from a cloud-based service. You might find that the service doesn’t deliver the kind of functionality that users expect. You might find that the costs of the service are higher than you expect. Your company might be taken over by another company that has a successful and cost-efficient in-house deployment of Exchange that they want to continue to use. Or you may decide that transferring email to Microsoft Online creates a lock-in situation that you are not happy with.

In whatever circumstances you face, it is simply good sense to figure out what your back-out plan will be if you need to use it. Think through the different scenarios that might occur over the next five years and chart out your response to these circumstances so that you have an answer. That answer might be flawed and incomplete, but at least it is an initial thought on how to approach the problem if it occurs. Apart from anything else, thinking about how to retreat from the cloud might inform your thinking about how to enter the cloud in a way that reveals new issues that you need to include in your implementation plan. For example, ask yourself how quickly you can move mailboxes back to an in-house infrastructure. Your company could go through periods of merger and acquisition so you need to understand how mailboxes can be moved out to be ready to be transferred along with the assets of a company that is sold or indeed how to merge in new mailboxes from acquired companies, including those who run non-Microsoft messaging systems. How can you transfer Lotus Notes mailboxes or Gmail mailboxes? How can you synchronize calendars with a newly acquired company without moving the infrastructure used by that company to Microsoft Online? While it might seem natural to move a newly acquired company to a joint platform as quickly as possible, laws in certain countries might slow the pace of a merger and force the maintenance of dual infrastructures for extended periods.

Another good debate to have concerns headcount.While you might need to reduce the number of messaging administrators to support a cloud solution after your migration is complete, maybe you should keep some in-house messaging expertise in place just in case you need to reverse course. Having its own expertise available allows companies to continue to track the evolution of Microsoft Online and solve synchronization and other administrative issues that you can expect ongoing operations to throw up. Not having to bring in expensive consultants is also a good thing when dealing with common messaging scenarios such as merger and acquisitions, the recovery of lost email, legal search and discovery, and so on. It is a good idea to review the out-of-norm scenarios that have occurred in the current messaging infrastructure over the last few years and determine a list that can be checked against the online environment so that you understand what the hosting provider can do, what your company will have to do in each circumstance, plus the expected SLA that the hosting provider will sign up for.

One small problem with the cloud analogy

The proponents of cloud computing eagerly seize on the notion of utility as the cornerstone for price reduction. Utility services such as electricity, gas, or water are pointed to as the metaphor for cloud computing. However, the question that needs to be asked is whether email or other collaborative applications process the same kind of dumb commodity that flows through electricity wires or water pipes. The answer is that collaborative applications do not. Instead, the data that people share and work on with applications such as Exchange often represent some of a company’s prime intellectual property and you cannot compare that data with a utility commodity that can leak or otherwise disperse en route between a generating station and its end consumer. In short, the data manipulated in collaborative applications is neither dumb nor disposable and cannot therefore be compared to the output of normal utilities.

Rushing to embrace cloud-based applications is dangerous unless you can assure that the utility platforms can deliver applications in such a way that your data is preserved, secured, available, and never compromised. By all means, exploit principles such as automation and standardization that underpin cloud computing to reduce cost and improve service, but always keep an eye on the balance between cost and value and don’t allow a race to the bottom to develop that impacts your ability to deliver world-class IT to users.

The cloud in the future

Cloud services are a major influence over the future delivery of IT to end users. The question is how quickly different organizations are able to embrace and use the cloud and what challenges exist along their road. The choice to use an online email service will be easy for some organizations, especially those who either don’t have an existing email service or who don’t make any customized use of their current email service. Things get a lot more complicated the longer an organization has been using email, the more mailboxes they support, and the better email is integrated with other applications. In these situations, you may find that online services are just a little too utilitarian in nature and that a more traditional outsourced or in-house deployment (hopefully one that takes advantage of cloud delivery principles to reduce cost) continues to meet your needs better.

, also available at Amazon.co.uk

. The book is also available in a Kindle edition

. Other e-book formats for the book are available from the O’Reilly web site.