Have you heard about a migration to modern public folders that has gone well? I haven’t. Apart that is from the demo migrations that appear at trade shows and conferences to show that all is well and that Microsoft hasn’t reneged on their promise to bring the cockroaches of Exchange kicking and screaming into the world of highly available mailboxes.

Microsoft has published a public folder migration checklist and written a number of scripts to support that checklist that you can download from their site (the scripts are also available in the $ExScripts folder on an Exchange 2013 server). The scripts support migration from legacy environments running on Exchange 2007 or 2010 servers to Exchange 2013 on-premises or Exchange Online (Office 365).

In theory, the procedure is straightforward.

- Wait until all mailboxes are moved to Exchange 2013. This step is mandatory because whereas Exchange 2013 mailboxes can access legacy public folders, the reverse is not true.

- Enumerate the legacy public folders and hierarchy and create a CSV file using the Export-PublicFolderStatistics.ps1 script.

- Examine the CSV output (a list of public folders and their sizes) to decide whether any adjustments need to be made. Pay attention to the limitations of modern public folders to make sure that you keep under whatever the currently documented limits are (250,000 folders and rising) after the migration is complete.

- Run the PublicFolderToMailboxMapGenerator.ps1 script to process the CSV file containing details about the legacy public folders and to map them to new public folder mailboxes. Essentially, the script attempts to break up the folders and divide them in a logical manner across a new set of public folder mailboxes. You control how many mailboxes are necessary by setting a maximum for the size of each mailbox. For instance, if you have 100GB of legacy public folder data to migrate, you could set the maximum size to 10GB and end up with 10 public folder mailboxes.

- Review the CSV file to decide whether public folders have been allocated in a reasonable manner.

- Create the public folder mailboxes, taking care to place them in databases that are capable of supporting the load that user connections will generate after you switch over to use modern public folders.

- Create a public folder migration request (only one can exist at any time) to process the CSV file that maps the legacy public folders to new public folder mailboxes. The processing is similar to a mailbox move in that the processing is performed by the Mailbox Replication Service (MRS) in the background. MRS connects to a public folder database, enumerates what it finds there (like a source mailbox), and transfers the data to the target (in this case, the public folder mailboxes).

- When MRS has moved the data, it halts (similar to a mailbox move that is auto-suspended).

- If everything seems to be good with the PF move request, you lock public folders for the organization (which has the effect of disconnecting users from legacy public folder databases), tell MRS to complete the move with Resume-PublicFolderMigrationRequest, wait for MRS to perform its incremental synchronization to move the last remaining vestiges of data from the legacy folders.

Get-PublicFolderMigrationRequest | Set-PublicFolderMigrationRequest -PreventCompletion:$false

Get-PublicFolderMigrationRequest | Resume-PublicFolderMigrationRequest - Once MRS considers the move to be finished (the status shown by Get-PublicFolderMigrationRequest is “Complete”), you can validate that the data has been moved to the new public folder mailboxes by connecting to one of them with a test mailbox. Logically, you cannot connect to a modern public folder mailbox until the migration job is complete. The best way to do this is to run the Set-Mailbox cmdlet to override the normal mechanism used by Exchange to locate the public folder hierarchy using the command shown below. You can also run some scripts to compare what exists on the legacy side with what has been moved.

Set-Mailbox -Identity "Some Test Mailbox" -DefaultPublicFolderMailbox "PFMailbox1" - If you are happy that everything has been properly moved to the mailboxes used by modern public folders, you can commit the organization to using modern public folders by performing a final switchover. To do this, you make sure that all the new public folder mailboxes are capable of providing the public folder hierarchy to clients and then run Set-OrganizationConfig to update the configuration and switch from old to new.

Get-Mailbox -PublicFolder | Set-Mailbox -PublicFolder-IsExcludedFromServingHierarchy $False

Set-OrganizationConfig -PublicFolderMigrationComplete:$True - Have a beverage of your choice to recover while basking in the admiration of users who are now totally happy to be connected to the new, improved, and most modern of public folders.

Update 14 July 2014: As MVP Andrew Higginbotham points out, if you don’t do everything properly, you might end up by forcing all clients to see the infamous “The Administrator has made a change that requires you to restart Outlook.” Check out his blog for details.

It all sounds good. It all seems like it might even work. And it does, in a test environment where you have 10 public folders to migrate.

The procedure runs into difficulty when confronted by the average public folder hierarchy. Invariably, the hierarchy is old, badly organized, unmanaged, and contains enough rubbish to occupy several skips. The problem you see is that public folders have been around for a very long time and during their existence it is extremely likely that many people, both users and administrators, have had their fingers in the pie. Folders exist for no reason; folders exist that once had a reason but one that is now long forgotten; folders exist that contain useful information that no one knows about; and public folders exist that contain the greatest collection of old rubbish and corrupt items that you will ever encounter in your career.

And the good news is that the procedure as laid down will faithfully attempt to migrate all the old, unwanted, unhappy, unreadable, and undesirable information from legacy public folders to their new homes. That is, unless you take steps to stop this happening.

We know that a CSV file is generated in step 2 of the procedure to enumerate the public folder hierarchy and its folders. The CSV file contains two columns – folder name and folder size, so you end up with something like this:

“FolderName”, “FolderSize”

“\IPM_Subtree”,”0”

“IPM_Subtree\Contoso”, “248844”

“IPM_Subtree\Contoso\Departments”, “12487744”

“IPM_Subtree\Contoso\HQ”, “45254”

“IPM_Subtree\Contoso\HQ\CEO Office”, “147755”

“IPM_Subtree\Contoso\HQ\CEO Office\2007 Business”, “477444”

Reviewing the contents of a CSV file to identify folders that should be pruned from the hierarchy is a tiresome business if you have a couple of hundred folders to examine, especially when you don’t know a lot about the content of the folders, why they were set up, who uses them, and when they were last accessed in any meaningful manner.

But many hierarchies have a few thousand or more folders and the thought of having to go through the full set becomes something that would only excite a lonely monk in a cell on an island in the middle of the Atlantic. Most administrators would prefer to tear out their own fingernails than process this CSV file, which is a real pity because the big flaw of the migration process is that if you don’t take the time to prune, remove, and destroy old rubbish from the public folder hierarchy before MRS starts to move data, all of the rubbish will be moved.

You can’t even take the obvious approach of deleting large batches of folders from the CSV file in the hope that MRS will ignore them during the migration. MRS is pedantic and exact. It will migrate everything it finds in the hierarchy even if you remove all reference to a folder from the input CSV file.

The next issue is that old public folders have a habit of storing old items (naturally), some of which fall into the category of “malformed MAPI items”. In other words, they are corrupt in the eyes of modern MAPI clients and servers. Unless of course you are a genius and know how to how to choose servers that allow for such things, I don’t know of any… Legacy public folders are not to be faulted for storing this information. Folders store items and the items were good when they were stored. But MRS will complain if it encounters one of these “bad items” and they will be discarded en route to modern public folders. You control the tolerance MRS has for bad items by setting a bad item limit when you create the public folder migration request, but it’s easy to blow the normal limit (10 or thereabouts) that you might use for mailbox moves with the rubbish lurking in the deep and dank corners of old public folders. Eventually you can force MRS to process everything, but be prepared to lose some data and to restart the public folder migration request several times after upping the bad item limit.

The dirty little secret of public folder migrations is not that the process does not work. It does, but it is excruciatingly manual in nature and execution and requires more time and effort from an administrator than you might possibly imagine.

We have not yet seen many public folder migrations because few companies have yet completed step 1 to move all their mailboxes to Exchange 2013. We will see more as time goes by. The potential for pain is out there…

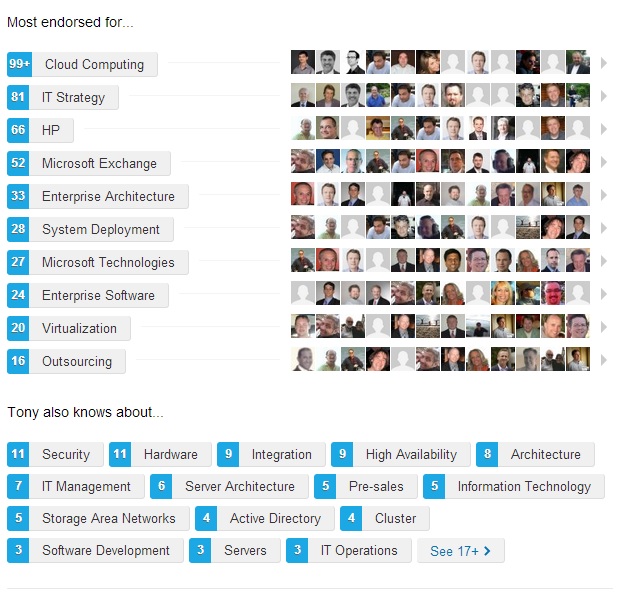

Follow Tony @12Knocksinna